Layne Staley wasn’t gifted with the power of prophecy, but he was keenly self-aware. The first song on Facelift, Alice in Chains’ seismic 1990 debut, is called “We Die Young.” 12 years later, at the age of 34, Staley was dead of a speedball overdose. His final years were bleak, and his death has proved mercifully resistant to the kind of romanticization that rock star tragedies often undergo. The overdose was the brick wall that he had been telling the world he was hurtling toward since the first time his inimitable voice was etched into the grooves of a record.

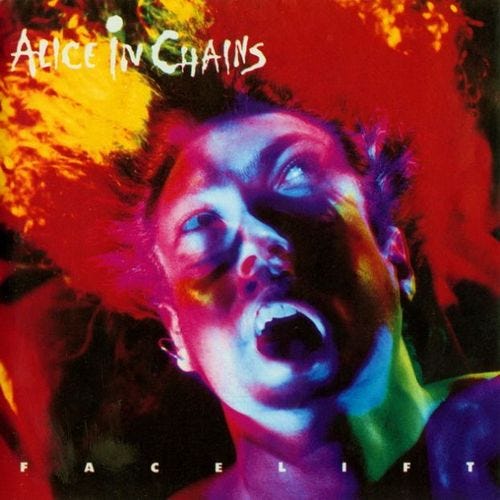

I had a poster of Layne Staley in my childhood bedroom. He was shirtless, gripping a mic stand and singing with his eyes closed, his birth year and death year hovering over his shoulder. I came to Alice in Chains shortly after Staley’s death, though even if I’d heard them while he was alive, I wouldn’t have had a chance to see them live. Their performance on MTV Unplugged, taped in April 1996, was their first show in two and a half years, and one of the last they’d play with Staley. He looks dazed and nearly comatose on that stage, rarely opening his eyes, grinding his way through his vocal parts while guitarist and duet partner Jerry Cantrell pulls most of the weight. Alice in Chains didn’t play any songs from Facelift during their Unplugged performance, which makes perfect sense. Unplugged emphasized Alice in Chains as a dark, depressing, emotionally devastating band. Facelift is too fun.

That’s not to say Facelift is fun, exactly. But it’s as close as Alice in Chains ever got. In 1990, there were still trace amounts of Staley’s former glam metal band, Alice n’ Chains, in their DNA. Grunge has historically been positioned as a refutation of glam, a salt-of-the-earth reaction to its excesses, and ultimately, the final nail in its coffin. Alice in Chains run counter to that narrative. Like Guns n’ Roses, their gritty yet glamorous hard rock was more an evolution of the Sunset Strip sound than an outright rejection. That’s especially true of Facelift, whose bluesier tracks sound like cousins of the deep cuts on Appetite for Destruction. Cantrell’s guitar tone was chunkier than Slash’s, but they clearly worshiped in the same church.

Before I go any further, I need to take a moment to sing the praises of Jerry Fulton Cantrell, Jr., my first real musical hero. The first tablature books I owned when I was learning guitar were for Facelift and Dirt. I bought a wah pedal – the Zakk Wylde signature Cry Baby, if you must know – just so I could play “Man in the Box” properly. His style was approachable enough for a kid learning how to play, but no matter how many times you practiced a riff, you could never make it sound quite like him. I didn’t stick with the guitar (I’m better at this, as hard to believe as that may be) but every time I consider picking it back up, my fingers subconsciously form the chords for an Alice in Chains song. Cantrell is a legend and a genius, and he deserves his flowers while he’s here.

On Facelift, you can hear the beginnings of the precious alchemy that the sturdy Cantrell and the mercurial Staley would soon perfect. On future releases, Cantrell would effectively be a co-frontman, but here, he mostly serves as an anchor for what would prove to be Staley’s most histrionic vocal performance. The call-and-response chorus for “Man in the Box” remains perhaps the signature moment in their partnership. Sing it with me: “Feee-ee-ee-eed my eyes! / (Can you sew them shut?) / Jeee-ee-eee-eezus Christ! / (Deny your maker).” They’d learn to wield their voices more tactically on songs like “Down in a Hole” and “Would?”, but the raw power they’d already discovered here is undeniable.

I mentioned earlier that Facelift is the fun Alice in Chains record. That’s obviously a comparative statement. Dirt is the bleakest, most fucked-up heroin album ever made; Jar of Flies and Sap are depressive episodes in audio; the self-titled sounds like a death rattle. (I’m ignoring the existence of the albums Cantrell, drummer Sean Kinney, and bassist Mike Inez made with William DuVall. I’m not usually dogmatic about new singers, but for me: no Layne, no AIC.) Facelift gets dark as hell, but even in its darkest moments, it allows for the possibility of light. “Sea of Sorrow” projects its wallowing onto a second-person recipient. “Bleed the Freak” starts despondent but breaks into a gallop. “Love, Hate, Love” ends back on “love.”

The real darkness of Facelift is in its foreshadowing. Once you know what happened to Layne Staley, some of his lyrical asides transform from bon mots into warning signs. “’Scuse the ’tude, but I haven’t eaten today;” “I’d like to have more of you in my veins;” “I don’t need you, I just can’t put you down.” Grimmest of all is “Real Thing,” the raucous album closer. If you’ve ever had a friend try to tell a funny drug story that ended up sounding more like a cry for help, then you know the energy Staley is bringing on “Real Thing.” He tries to borrow $50 from his rehab doctor to cop drugs. His friends try to save him from himself, but he mocks them and keeps using. He attempts to tie the whole thing up with a joke – “sexual chocolate, baby!” – but nobody’s laughing.

Two years after Facelift, Alice in Chains would release Dirt, a strong candidate for my favorite album of all time. By then, the party was over, the fun had curdled into self-destruction, and the band’s depressive tendencies were brought to the fore. It’s a better album than Facelift for all of those reasons, but it still feels uncomfortable to say that. If Layne Staley had been able to get a better handle on his substance issues, we might not have gotten Dirt, but we might still have him around today. It’s fraught, to say the least. I think that’s why it still feels so good to listen to Facelift. It didn’t turn out to be the darkness before the dawn, but it could have been.

Next week: Beyond the blackened burning skies